For three weeks the thermometer outside the Hanover Inn has been near zero at dawn, making for a brisk walk for senior Tom McCoy on his way each morning to the lab he shares with Associate Professor Catherine Cramer in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences.

The cold of winter on the Hanover Plain is no match for the burning ambition of undergraduates, such as McCoy, intent on making the most of Dartmouth's unparalleled classrooms, faculty mentorships, independent studies, and even partnerships with the graduate and professional schools.

Although it's a less commonly known part of the Dartmouth academic world, the ready access undergraduates have to the Arts and Sciences Graduate Program, Thayer School of Engineering, Tuck School of Business, and Dartmouth Medical School is reflected in course work and independent study currently being done by a number of students. The “academic continuum” is how Paul Danos, dean of Tuck, describes it.

“The faculty in the professional and graduate schools have an affinity for the undergraduate,” says Albert Mulley MD, '70, a member of the Dartmouth College Board of Trustees who researched the undergraduate academic experience in 2004–2005 for the board's Working Group on Academic Excellence. “They're enthusiastic about giving undergrads opportunities for teacher–learner intimacy, interdisciplinary knowledge creation, and innovation. It's a result of the good job Dartmouth does in recruiting faculty who are committed equally to teaching and knowledge creation.”

And who are one body. Dartmouth doesn't have separate graduate and undergraduate faculties, so not only are all undergrad courses except a couple in the Math Department taught by faculty, but undergraduates may find themselves being taught by faculty with appointments in the professional programs—including the dean.

As senior Brian Christie has, in Global Health and Society, a new course offered by the Department of Geography to first-year students on up. Taught by Dr. Lisa Adams, assistant professor at DMS and coordinator of the Dartmouth Global Health Initiative, and Dr. John Butterly, associate professor at DMS, the course incorporates classes guest-taught by Dr. Stephen Spielberg, dean of DMS, and a number of other faculty .

“Geo 2 is absolutely fascinating,” says Christie, a premed English/creative writing major. “My best friend from high school, who's at Penn, and I want to take a year off to volunteer in clinics in Africa before we go to med school, and this course is exactly the background I need—what's going on epidemiologically with TB, malaria, and HIV/AIDS in Africa and Asia, and the U.S. role in that. There's not a lot out there that pulls this information together the way this course does.” In addition, Christie has a leg up on volunteering through Dr. Adams's connections in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, where the DarDar Clinic is run by the DMS Infectious Disease and International Health section and the Muhimbili University College of Health Sciences.

The Dartmouth academic continuum is fully exploited by students doing Presidential Scholar research or writing an honors thesis. Since 2000, more than one-third of Presidential Scholars have pursued their studies in departments with graduate or professional degree programs, experiencing Dartmouth's superlative faculty mentorship framework in both the undergraduate and graduate settings and undertaking research as an integral team member or on their own. They've often seen their name in a byline below the title of a journal article; they've learned what questions are being asked at the frontier of a field; and, not least of all, they've had a good look at what life as a graduate student is like.

“In many cases, undergraduates are treated more like graduate students and have the opportunity to be involved in high-level research,” explains Margaret Funnell, assistant dean of faculty for undergraduate research. “Because Dartmouth graduate programs are small, undergraduate students aren't separated from the principal investigator by a hierarchy of graduate students and postdocs.”

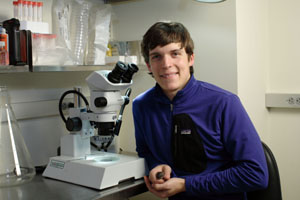

to find out in an original, graduate-level study in which he's the

principal investigator. (Photo courtesy of Tom McCoy)

And sometimes they are the principal investigator. McCoy, for example, is carrying out an entire, original study on the monogamous behavior of male prairie voles: He's writing grants; developing protocol; completing required paperwork; running experiments; analyzing data; and, in the spring, writing a thesis.

“Having Professor Cramer accessible is really what has made it possible for me,” says McCoy, a philosophy/neuroscience double major. “When professors agree to sponsor an aggressive thesis that isn't library based, they're committing their personal laboratory funding and space. Professor Cramer gave me almost her entire lab to run experiments and committed funding above the grants I was awarded. Even more important, if you're going to bite off more than you can chew, you've got to have an advisor who is around, accessible, committed, and willing to help you at the drop of a hat.”

Professor Cramer helps him with anything, says McCoy, from the mundane—where to find nesting materials?—to running experiments for him when he travels for medical school interviews, to “vetting a list of a hundred ideas.”

Says Cramer, “I'll tell him, ‘With these questions, you're guesstimating—maybe they'll work, maybe not—but with these others, you're showing understanding, and with these others, you may contribute to the knowledge.” She pauses and adds playfully, “That's code for ‘publishable.'”

“There's a difference,” says Cramer, “between being in a teaching lab, where you're reproducing someone else's results, and doing a thesis. With a thesis, you're researching the true unknown.”

A Philosopher A-Mazed by Science

Professor Catherine Cramer and senior Tom McCoy, sitting in her laboratory in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, talk to and about each other with the slightly tired, wired, companionable energy of colleagues who share a fervent dedication to their science, a vision of how it's best done, and great daily working rapport. It takes a visitor five minutes to forget that McCoy, who is researching the social behaviors of prairie voles, is an undergraduate.

He came to Dartmouth, McCoy says, “with a vague interest somewhere between cellular neuroscience and social psychology,” and, intrigued by social systems and planning to write a thesis, he majored in philosophy.

“In my sophomore spring, there was an 11-hour I planned to take, but when I went to the first class, I knew I wasn't going to like it. There was a class next door at noon, so I went to that one.”

The class was Cramer's Psych 52: Animal Learning and Behavior, and “it was great,” says McCoy. “She's good in front of a class. Really good. We learned about operant conditioning and the social systems of voles and other rodents, and I left thinking, I'm really interested in this!” Studying animal social behavior was, as it turned out, the perfect fit for a psychological-minded young man who grew up on a farm, and McCoy promptly added a neuroscience major. After the course, he went to Professor Cramer's office and said, “I'm interested in working in a lab. Can I work in yours?”

“I said, ‘Great!'” recalls Cramer, whose research is on how rodents' early-infancy behavior, such as suckling, affects their later brain development, such as spatial learning.

McCoy knew then what he'd devote his thesis to.

“Being rodents, prairie voles are an example of animals held in low regard by most people, but they exhibit complex social behaviors. Unlike most other mammals, they're monogamous. Why? What pressure is this behavior in response to?”

He started “writing baby grants” and working on the protocol and paperwork for a study of how their mate's presence affects male prairie voles' behavior. Does it make them less anxious? More anxious? Does it affect their learning?

“Setting up the protocol has been a big part of the learning experience,” he says. “You read a journal article, and you see one phrase reporting the use of a radial maze. As an undergrad, without actually doing it, you don't know that it takes all day, or longer, to set this up. Now I know: the devil is in the methods section. If you're going to find a mistake, it'll be there.”

“One of the interesting aspects for faculty,” says Cramer, who, as undergraduate chair, advises all PBS majors, “is determining how loose to cut a student. You gauge this by watching how the student handles the day-to-day jobs.”

and Cramer make a great team. (Photo: Kawakahi Kaeo Amina

'09)

McCoy is now in the experiment phase of his study, videotaping voles in mazes; when's he's finished, he'll have about 750 data tracks to analyze.

“Those research posters in the halls?” he says. “They seemed a little juvenile to me at first, coming as I did from a humanities background. Now I know that generating the contents of even one bar graph is huge. I have an all new appreciation of the research poster.”

“My interest is in ideas, questioning, and process," says Cramer. "For me, good science is idea centered rather than simply results centered. My metric is a good idea tested, and tested well, and the process of doing science learned.”

“It's only once you take on the additional responsibility of doing the science,” says McCoy, “that you can appreciate the nuance of science. Professors who answer a question, ‘Well, . . .' used to drive me nuts. I just wanted a straight answer. But once you start doing the science, you can't see it any other way. You know the difference between the answer and the field.”